Why you hate modern movies

Everything you ever thought but couldn't articulate because the problem is so massive in scope

You hate modern movies. It’s okay to admit that. By “modern,” I mean “movies made in roughly the last 20 years or so,” say beginning around 2003. That’s roughly the starting date at which a sort of cinematic shift seems to have occurred, one in which the priorities and presumptions of the filmmaking class shifted in a notably definable way.

For some reason many people tend to be really hostile towards and resistant to claims that the present cinematic landscape might be both (a) different and (b) worse than that which came before it. Whenever I write critically about modern films, two kinds of responses tend to proliferate: In one case, readers will argue something like: “Every generation venerates the art it grew up with and criticizes new kinds of art. This is the same thing. Movies today aren’t worse, they’re just different.” In another, respondents will say something like: “It’s ridiculous to make broad claims about movies being bad these days. Tons of good movies are still being made, you just have to look for them.”

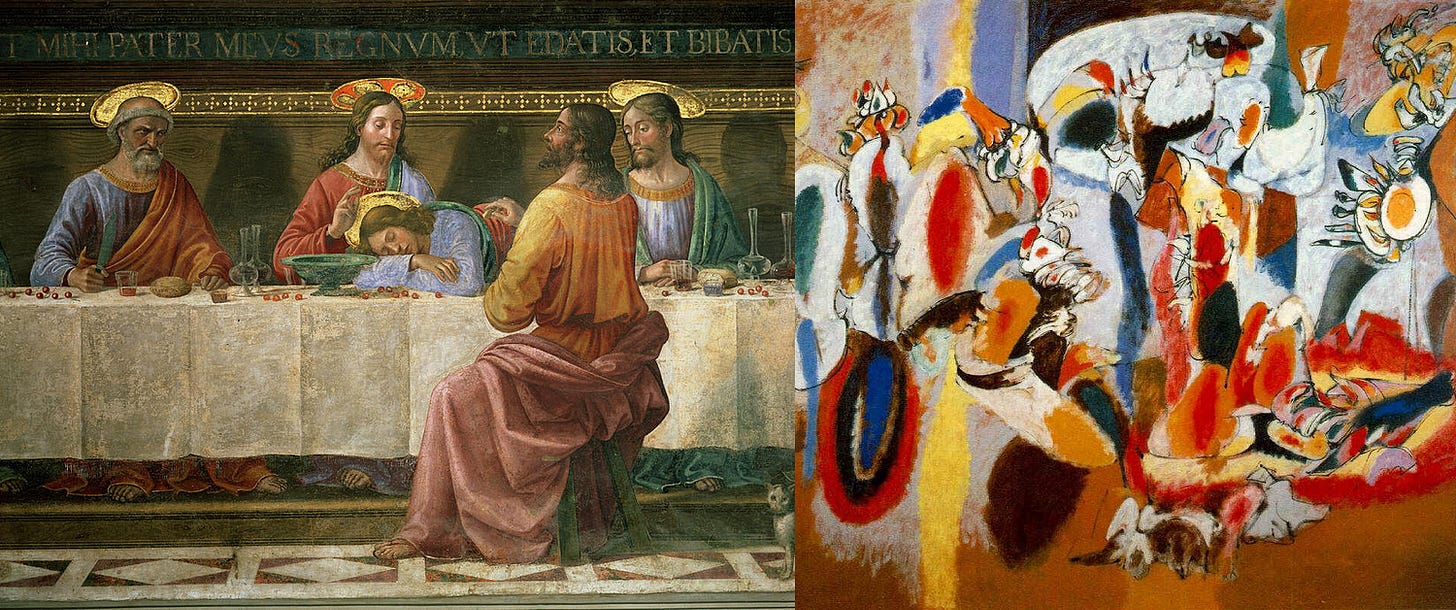

The first argument is a lazy evasion, the sort of thing you say when you kinda know the other guy has a point but you’re too slothful to put much thought into criticizing it. Yes, older people tend to criticize new pop culture while arguing that the older stuff was superior. What exactly is the point here? That everything is relative? That quality is ultimately a meaningless signifier and we shouldn’t argue about the relative merits of anything, ever? Is there anyone who honestly thinks that a Burger King building is more architecturally inspiring than the Chrysler Building? How many people do you think will sincerely argue that there is no qualitative difference between Italian Renaissance art and abstract expressionism? How seriously do you think you should take those people?

Don’t feel bad about staking out a definitive opinion on aesthetic things. It’s okay to do that. It’s okay to have emotional responses to negative stimuli. It’s also okay build logical, well-reasoned arguments about why you think some art is good and other art is bad. Lots of people will get mad at you if do this—rather than debate the merits of the argument, they’ll just claim that you shouldn’t have an argument at all, that we shouldn’t even be discussing this sort of thing and we should all instead just sort of, I don’t know, uncritically accept everything we’re given, never really talk about anything at all, and just leave it at that. Okay.

To the second counter, that good movies are “still being made” and one merely has to hunt them down to find them, well, for the sake of argument let us so stipulate. That is wholly beside the point. When we criticize modern cinema we don’t do so with an eye to absolute universal critical condemnation. We couldn’t possibly assess the merits of every single movie being made; that would be impossible. Nor are we necessarily even arguing that there is properly construed a total absence of actual good movies. Presumably there are at least some decent ones being made out there. The point is rather that popular cinema—the form of moviemaking that is most readily accessible to the most people—has declined significantly in value relative to what it was a short number of years ago. More specifically, the point is that popular cinema used to be really good, that the most popular and widely seen movies were regularly of both high artistic value and high entertainment value, and that the spaces that used to be occupied by these movies are now taken up by really very awful movies of essentially zero artistic merit and vanishingly little entertainment quotient.

Here’s a useful analogy: Imagine that, say, the vast majority of the restaurants in a city started offering nothing but literal dog shit on their menus. Every restaurant just served up pile and piles of dog crap, every item on the special board was dog crap, the desserts were literal dog crap, just all dog shit, all the time. Now, a reasonable person would look at this culinary landscape and say, “Wow, this city has an absolutely horrific dining scene. It’s just dog shit everywhere you go. Everyone is sick and the whole town smells like a dog’s ass.” Imagine the sneering counterpoint: “Um, the dining scene here is actually still really good. You just have to work hard to find the restaurants that aren’t serving piles of dog crap. They’re a lot harder to find now, but they’re still out there. It’s not right to say that the city has a bad dining scene, you just have to put in the work to find it.” Obviously this is a laughable sort of dodge. If a particular industry is pretty well guaranteed to serve the consumer a bunch of literal sewage in the course of a normal transaction, the industry has a big quality problem. No need to pretend otherwise and no need to take seriously those who do pretend otherwise.

Critics can claim that the present movie landscape simply isn’t that bad. But they cannot deny, without looking very foolish anyway, that the present movie landscape has changed, that there has been a major tonal shift in movies in recent years, that filmmakers are following a set of artistic presumptions and impulses that were largely not present in years and decades past. Why deny this? It’s true of every decade of any kind of art or craft, after all. The music of the 1950s was not that of the 1980s; the popular novels of the 1960s were radically different from those of the 1930s; the architecture of the 1890s was, in case you hadn’t noticed, radically different from that of the 2020s, unfortunately. You can debate whether or not the riordinamento is good or bad, but you can’t really argue that it hasn’t happened. It always does.

But why is it bad? At its most basic level, modern cinema is a miserable failure largely because it has ceased to be recognizably human.

What I mean by that is that the normal markers of popular cinematic art that distinguished it as a human enterprise—a form dedicated to studying and exploring and celebrating the dimensions and components of humanity and the human person—have all largely vanished or are vanishing. What has replaced them is a set of creative compulsions that are less geared toward the human and more geared toward a kind of checklist of pseudo-artistic abstractions.

This change does make business sense. You can’t deny it. Modern movies, especially the ones that are really modern, make a lot of money. Even the ones that don’t make as much money still make a good bit. There’s a winning formula at hand here. And movie studios very much love winning formulas. They don’t like to take gambles. Of the top 10 highest-earning movies last year, nine were sequels—ten if you count “The Batman,” the third or fourth reboot of the Batman franchise in the last 15 years. Sequels have always played well with audiences, but their comprehensive dominance at the box office in recent years suggests an exacting refinement on the part of the film industry to do away with real artistic creativity and exploration in favor of very predictable, low-effort, low-stakes filmmaking that makes a lot of money.

The modern cinematic aesthetic dovetails nicely with this impulse toward recycling. Sequels make money because they’re familiar and predictable. Modern filmmaking in general—whether sequel or not—is also very familiar and predictable, its methods and signifiers instantly recognizable, its forms increasingly universal among most popular movies. Cinema is increasingly refining itself to a narrow set of artistic patterns that have erased much of the distinctions between individual films and genres. More and more everything looks and feels the same. And most importantly, it all looks and feels really bad.

It is necessary to provide examples of this analysis—to demonstrate what exactly it means when a movie ceases to be human-oriented in any meaningful sense. Attacking a problem of this scale is never going to be an encyclopedic endeavor; the problems are system-wide and the solutions are necessarily going to be systemic, which means any one illustration is always going to seem demonstratively insufficient. A critic can look at these and think, “That’s it?” But we know it’s more than that. We know modern movies suck. And ultimately we know why. Here’s why, in no particular order:

Everything moves too fast. Modern movies are too fast. They just move too quickly. I don’t meant that they’re too short; in fact the average runtime of most popular movies has increased considerably over the last few decades. What I mean is that movies made today very often feel completely rushed, as if the filmmakers are just completely impatient to get through each scene, either in principal photography or post. A movie today often feels like it’s being told by a five-year-old trying to explain his favorite video game: Just a breathless narration without any real concern for how poorly it all gets transmitted.

Here’s an example of both a well-paced movie sequence and its poor present-day counterpart. Consider this scene from the superlative 1993 Jurassic Park, this in which the two primary protagonists Alan Grant and Ellie Satler first meet deuteragonist John Hammond at their Montana dig site.

The pacing and structure of this scene is really very apt. The long shot of Grant loping from the helicopter to the trailer allows us to appreciate the scale of Hammond’s outwardly rude intrusion into the site; the pan into closeup on Hammond—and the explosive uncorking of the champagne—illustrates that his presence is consequential and meaningful; Grant is struck dumb for nearly 10 solid seconds at Hammond’s introduction, further underscoring the significance of his arrival. We learn a great deal about all three characters in less than a minute: Alan and Ellie are fiercely protective of their work and prone to hotheadedness; both of them are smart enough to recognize when to dial it back; Hammond is unflappable and confident and genial. In about 50 seconds we have valuable information about three key characters that will inform our interpretation and enjoyment of several critical subsequent parts of the film. We learn all of this because the filmmakers utilized the screentime in a careful, deliberate, measured way. They took their time.

Now consider a contrasting scene from Jurassic World: Dominion, the fifth sequel in the film series, released in 2022:

This is obviously meant to be a sort of mirror depiction of the sequence from 1993: Alan comes into his dwelling and finds an unexpected visitor there, one who radically changes the course of his life. But it falls so completely flat, in large part because it takes no time at all to demonstrate the significance of Ellie’s reappearance and the reunification of the two characters. The audience, after all, is led to believe that the last time these characters ever interacted with each other was in 2001’s Jurassic Park III. Their meeting each other again after more than 20 years should play out with more length and gravitas than this—more, anyway, than the two of them uttering each other’s names in awed, serious tones before launching into small talk. Grant should be curious as to why his old paleontologist partner and lover has showed up in his tent in the middle of the Utah desert, and he should pursue that curiosity carefully. This should be a bigger event in his life than “(deep breath) Ellie Satler.” Remember what I said about movies not being human anymore? This scene—and the rest of the movie, which plays out with a nearly identical shallowness—isn’t human. It’s not how real actual humans would react. It’s too quick, too simplified, too awkward, too inorganic. It’s weird and unsettling.

Beyond that, consider the technical pacing of the respective scenes: In roughly one minute, the 1993 sequence has a total of five standard cuts. In just over 40 seconds, the 2022 scene has 13 standard cuts. So in about 20 fewer seconds, the later scene has nearly three times as many cuts as the earlier one. The product of the former feels careful, normal, thoughtful, very human-paced; the latter feels like a video game or a slot machine, just an ongoing march of stimuli in which you can never focus on a single part.

This isn’t idiosyncratic to the miserable Dominion or even to a large handful of movies. A few years ago James Cutting, a psychologist at Cornell, gave a presentation at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in which he demonstrated the staggering reduction in shot lengths over the last century of filmmaking:

The average shot length of English language films has declined from about 12 seconds in 1930 to about 2.5 seconds today, Cutting said. At the Academy event he showed a scatter plot with data from the British film scholar Barry Salt, who’s calculated the average shot duration in more than 15,000 movies made between 1910 and 2010. …

The graph in question provides an undeniable visual example of the decline in shot length:

Shots are indeed getting shorter and shorter, contributing strongly to the sort of rapid, chaotic element that feels present in so much popular cinema these days. But as we’ve seen, it’s not just the shot length that matters, but what do you within those increasingly narrowing windows too. And another great example of modern cinema’s failure in that regard is found in a comparison of 1996’s Independence Day and its 2016 sequel Resurgence.

Near the end of the earlier film, secondary character Russell Case is taking part in the last-ditch desperate counteroffensive against the genocidal alien invaders. He moves to fire his final missile at the imminent alien superweapon, only to have it jam on him; he subsequently decides to mount a kamikaze run against the ship in a Hail Mary attempt to stop the weapon from firing.

We are not doing a purely critical analysis here so I will not dwell on just what a truly masterful hero sequence this is, how every aspect of this scene drives the viewer toward a sort of thrilling enjoyment of it, from the swelling federal-style orchestral arrangement to the character’s triumphant strike at the heart of the enemy, the hero himself a grinning, exhilarated warrior filled with pure confidence at both the rightness and the guaranteed success of his mission. It’s effectively perfect in that regard. It’s just so good. But it would fall flat if it were not done right, and it most assuredly is done right. A full 20% of this scene passes before Russell even begins his victor’s run; we are given such ample time to see him ponder his decision, and with him we savor and appreciate the weight and the consequence of it all. When he resolves to do it, it still takes a decent amount of screentime for him to accomplish his mission. Even as he’s barreling straight toward the plasma cannon a mere several hundred feet from his objective, his comrades in the sky are still wishing him luck and his comrades down below are still demonstrably in mortal peril. The viewer is given such profound understanding that Russell’s sacrifice is just completely timely, the absolute last chance, a tiny opportunity which he seizes and at which he ultimately, incredibly, succeeds.

The 2016 sequel, which I do not hesitate to say is one of the most unfortunate movies I have ever sat through, attempted to replicate this magnificent accomplishment in its own right, and in doing so it…well, have a look.

I saw this movie in the theater and I do not mind saying that by this point in the film I was beyond caring what happened in any of it. Furious at having wasted money on a dismal movie and extremely nauseous from having consumed effectively an entire jumbo tub of popcorn, I just wanted it to be over so I could go home. But even in that angry sort of haze I recognized just how truly hollow this sequence really is. For starters, as with its counterpoint scene in the dinosaur movie, this one crams a staggering number of cuts into a relatively brief screentime. The 1996 clip is 1:22 in length and contains a total of 15 standard cuts; the Resurgence clip is 1:35 and contains, well, I genuinely lost count but I think it’s around 60 cuts. The 2016 sequence is just 15% longer, in other words, and yet it contains 300% more shots than the 1996 one. Bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam, just nonstop cutting, you can never focus on any one thing, the action is always being redirected toward other action, it’s just a frantic, frenetic avalanche of stuff you can never fully process, much less enjoy.

More importantly, the movie just completely misses the necessary pacing and careful presentation that makes an arrangement like this compelling and affecting. Whitmore’s entrance into the alien ship happens so quickly, and without any meaningful cinematic indicator, that when you see it you’re not even sure that something important has happened. His arrival proper before the alien queen—a moment that should be filled with both dreaded consequence and fearful gravity—is not at all punctuated in any noticeable way relative to the rest of the scene; he just rises up in front of her, things keep going, nothing sets it apart from anything else that’s happened up to that point, the action just speeds on ahead. His send-off line is rushed, delivered with no force, of any kind, whatsoever. The explosion of the enemy ship is similarly pallid. The explosive climax in the earlier film was triumphant and protracted, lasting a total of about 13 seconds of screentime so you could fully appreciate Russell’s accomplishment. Here it is rapid and ineffectual enough to be meaningless: The explosion itself is initially shown for literally half a second, and at no point does the movie really fixate on it in a way that communicates that anything of any significance has happened at all. It’s all rushed, relentless, nonstop, ever-frantic, never-focused.

That’s how it is with much of modern cinema these days. That’s how it always will be when your shots get increasingly shorter and your artistic impulses are geared toward action without development and activity without real meaning. Consider as another example this emblematic scene from 2018’s Bohemian Rhapsody; this sequence was critically maligned for how poorly edited it was, although it is in many ways pretty par for the course for modern filmmaking:

This scene is so chaotic and disjointed enough to be effectively incoherent; it is at least disorienting to the point that you’re not really sure if you’re missing something and you feel unsettled enough that you can’t follow along. This is not rare in present-day cinema; it is common.

Modern movies increasingly all look the same, and unpleasantly so. Modern movies have a weird uniform look to them. There are two qualities to this uniformity: The way movies are produced, and the way they are styled.

a. Production: Essentially every major film produced today is shot in digital format. Filmmaker Magazine Editor Vadim Rizov wrote in 2019 that just 24 major films in 2018 had been shot on 35mm. There’s no reason to think those numbers have improved in the past five years. Film is more expensive, more cumbersome, it requires greater finesse and greater technical understanding at every level. Digital is cheap and abundant and the bar for mastering it is much lower. So most filmmakers opt for digital today, with the depressing result that most films look pretty much identical to each other.

At this point you might say: “Wait a second. Why should digital make everything look identical? After all, decades of celluloid cinema didn’t make everything look identical. What’s the difference?” The difference is that digital has a queerly homogenizing effect on picture quality; it functions as a qualitative steamroller that flattens the onetime-common distinctions between movies. Digital makes everything look too perfect. It erases the regular differences in films that let us fully appreciate different cinematic styles and different qualities of the depictions we see on screen. If everything is filtered through a prism of hyper-detailed, crystal-clear ultra-high resolution, it’s going to iron everything out into a kind of generic blandness.

Ari Mattes, a film lecturer at Notre Dame, wrote several years ago of the “flat and depthless” quality of much of digital film:An old black and white film, shot on celluloid, has a grainy texture that draws the eye into and around the image. This is partly the result of the degradation of the film print, which occurs over time, but primarily because of the physical processing of the film itself.

All celluloid film has a grainy look. This “grain” is an optical effect related to the small particles of metallic silver that emerge through the film’s chemical processing.

This is not the case with digital cameras. Thus video images captured by high resolution sensors look different from those shot on celluloid…The edges look too sharp, the shades too clearly delineated — compared to what we have been used to as cinemagoers.

Mattes cites as an example the recent Netflix film Mank, about Citizen Kane co-writer Herman Mankiewicz; this film is shot in black-and-white with the intent to give it an older feel, but with digital it comes out looking and feeling unmistakably modern, and—importantly—identical to how most other films look and feel:

Everything is too defined, too precise. It looks like the visual equivalent of a gay Broadway play: It’s too loud, too annunciated, everything clicks at right angles and primary colors. It doesn’t look like real life; real life is full of blurs and visual uncertainties. It doesn’t look—what’s the word?—human.

Consider the visual contrast with this unfortunately timely scene from It’s a Wonderful Life:

It is immediately evident how much more realistic this scene looks and feels compared to its present-day digital counterparts—it is far more warm, inviting, recognizable. Celluloid’s medium feels far closer to the medium of exchange going on inside our optic nerves. Old film allows your eye to pause and to get comfortable. Your eyes glide over the screen instead of jagging over it, they can come to rest, they can find shades and tones that don’t feel like they came from a Frank Miller comic book. And that sort of normal, lifelike variance in visual tone means that movies shot on film will stand out as unique and idiosyncratic in ways they simply don’t on digital.

b. Style. I don’t know if this is just a function of the unbearable crispness of digital, but it seems like most popular filmmakers at present go to really great lengths to make the aesthetic style of their films as fake as possible. Most pointedly, people in present-day movies really just look too good. It’s just unsettling how duded up everybody always looks in movies today.

Here’s a great example of contrasts. First, a scene from the 1987 comedy classic Overboard:

It is true that some of the styles are dated here, but really not by that much, and in any event 1980s rural chic has sort of come into fashion again so much of this is recognizable. But beyond any temporal dislocation, the appearances of everyone and everything here are…normal. The people just look like normal people, recognizably normal, like people you might encounter at some point in your life; the clothing looks normal, like clothing you’ve worn at some point and will probably wear again at some point; the hospital looks like a normal facility, a bit rural but definitely like a building you’ve been in before. I don’t want to belabor the point here, but it all just looks normal. Actually I do want to belabor that.

Here, meanwhile, is the relevant scene from the 2018 gender-swapped reboot:

Notice how unsettlingly crisp and unsullied everyone and everything appears? As if all of these people and things just appeared fully formed, pristine, almost counterfeit, like they were baked over a light bulb in an Easy Bake Oven? I think the unbearable crispness of digital explains some of this, but not all or even most of it. This movie looks as if it was made by people who have never encountered used clothing before, and who have never been inside a building that wasn’t lit by HID floodlights. The walls look like they were just painted the day before; the hospital looks it was made for the fake 1950s-style idealized television town depicted in The Truman Show. Everyone is much too free of wrinkles and blemishes and normal markers of humanity. This movie almost feels like a sort of meta-commentary on movies altogether; it feels like a movie set of a movie set, as if its creators are seeking to lampoon the ultimately counterfeit nature of film itself.

I have made the following comparison before, but it just seems apt enough to reuse it again here. Here’s a scene from the 2022 movie Till, which is primarily about the life of Mamie Till after the brutal, psychopathic 1955 murder of her son Emmett in Mississippi:

As before, everything is too bright, too primary, too aggressively off-the-screen. This does not look like the bedroom of a boy in 1950s Chicago; it looks like a Disney World version of that, purpose-built, never actually used, disquieting in its existential emptiness. The door looks like it was hung yesterday; the lamps look like new Bondi Blue iMacs; Mrs. Till’s dress looks like it should be behind glass in a Smithsonian exhibit on Studio Era Hollywood. It looks like the filmmakers never studied anything about 1950s aesthetic, or black American history, or anything about how to make a film appear not unnervingly fake. Real people do not live in these environments; human beings have never occupied this bizarre sort of Asgardian plane of gleaming scrubbed perfection.

Here in comparison is a brief clip from the fantastic 1991 Southern drama Fried Green Tomatoes:

Now, there are some minor caveats here: The South in the 1920s will obviously be presented differently than Chicago of the 1950s, this is an outdoor rural scene rather than an indoor urban one, the people in this scene are wearing their working clothes rather than their traveling best, and so forth. And yet there is an obvious fundamental difference, at the stylistic and conceptual levels, to how the respective filmmakers decided to present a basic, normal scene featuring normal people. The 1991 scene is recognizable at a familiar, elemental level. You have been here before: At this barbecue, with this man, in this town, under this canopy. You recognize it because the filmmaker elected to tell a story using recognizable elements of place and person. None of what happened in the movie actually happened, but you can at least picture it happening in the way it did, because it plainly takes place in the real world.

I wonder if the problems of both digital film and synthetic-looking movie aesthetics are kind of intimately connected. Perhaps filmmakers are gambling that digital film’s razor-sharp clarity and resolution is only tolerable if the cinematography is cleaned up to reflect that factor: Digital film might inadvertently magnify every single flaw and feature of anything it captures, so everything is scrubbed and sterilized in order to make the visuals more palatable for the viewer. That’s a thought, anyway, though of course if it’s true then ultimately it fails completely. Movies today mostly look very trashy and very low-rent even though they’re shot using high technology and with exacting artistic precision.

Movie dialogue is very often irritatingly unconvincing and unfunny. Popular cinema has come to rely on a really unpleasant style of sort of hepcat, fast-talking, quip-laden form of talking to serve for most of its dialogue. Characters in popular movies are very often written to speak in rapid-fire, whip-smart, quick-with-a-comeback utterances; in so much of this you can always hear this vague undertone of barely concealed sarcasm and aloofness, as if the characters themselves are only half-interested in what’s even going on.

A number of critics have blamed this new cinematic impulse on the ubiquity of the Marvel comic book movies, in which this kind of humor proliferates to a shameful degree. I think that’s half-right. The Marvel films have done an obscene level of damage to modern popular cinema, and the deleterious effects they’ve had on screenwriting is part of that. But I also think the problem can be explained more fulsomely by the rise of social media, especially Twitter and TikTok. Social media greatly incentives the kind of smarmy lightning-fast repartee with which so many movies are suffused these days. People have come to expect it in their lives both on- and offline. Movies increasingly seem to be reflective of this desire, though they are doubtlessly informing it as well, in a sort of toxic loop of awful, endless nattering.

Here’s an example of this kind of grating dialogue, appropriately enough in one of those stupid Marvel movies, Avengers: Age of Ultron:

There is a very deliberate aesthetic here: Everyone is relaxed, cool, off-the-cuff, yet everyone’s on their best game, slinging with witty barbs and whip-smart comebacks. We’re meant to experience secondhand a kind of laid-back camaraderie, I think in part so we can picture ourselves doing the same thing with our friends. Many people want to picture their lives like this—the fast pace, the wisecracks, the group chuckling, the knowledgeable side jokes (“I will be re-instituting Prima Nocta”), the gentle harmless ribbing. There’s a reason that the YouTube comments about this scene are so ecstatic: “The amount of love I have for this scene is inexplicable.” “The most loved & realistic scene ever in the mcu.” “i bet the cast had a blast hamming it up in this scene- its so evident on their faces!” “I seriously still wish we got more scenes of the Avengers just hanging out as friends.”

Dialogue like this, which is increasingly ubiquitous in modern filmmaking, is meant to be a sort of canvas upon which moviegoers paint their own dreams and desires. Viewers look at scenes like these and say, “Man, I wish my life was like that.” Many of them likely do try and make their lives like this; we’ve all been in that group at some point or another. But it never works out. At some point the quips die out and the flow dies down and it’s suddenly kind of awkward that you’ve been spending the last fifteen minutes trying to make your life like a scene from a comic book movie. You can’t really sustain this kind of aesthetic; it’s not human.

Here, meanwhile, is a much more realistic sort of exchange, effectively the same setup as that depicted above—a group of people talking amongst each other on the cusp of a significant conflict—but one far more authentically and meaningfully portrayed, in 1975’s Jaws:

I will belabor again: Doesn’t this just feel more normal? Does it not feel like Spielberg simply understood the mechanics of real human conversation better than Joss Whedon? The atmosphere here is so instantly recognizable as something you yourself have experienced at some point or another. There are no pretensions here. These men are not precisely friends, not at this point or any point during the movie; they never slip into the sort of corny, saccharine back-slapping rapport so common to modern group movies. Rather they found themselves through happenstance in (literally) the same boat, they’re trading some funny stories and having a laugh or two, and that’s it. They don’t feel the need to flex by making some dim historical reference, there’s no corny quick-clip cutaway gags or awkward silences. You don’t look at this conversation and think, “Man, I wish I could do that;” you look at it and recognize, if only subconsciously, that you have done it. The movie uses a universal experience to deepen and appreciate its brief but compelling character study. It’s good.

Here’s another example. Consider the early scene in 1984’s Ghostbusters in which Ray rolls up with the hearse that will in short order become the Ecto-1:

This is a funny scene. It’s not that funny, because it doesn’t have to be. A car is a car and there’s no need to stress it too much. But it’s funny because it’s a normal gag juxtaposed against the sheer abnormality of a ghostbusting business. The car itself is a classic hunk of junk, which makes it funnier. It needs repairs on everything, it cost a ton of money ($4800 is very nearly $14,000 in today’s dollars), it’s a hearse—these are all good jokes, recognizable, universal, very human, a funny sequence in a very funny movie.

So of course the lady’s reboot from 2016 took a brief throwaway joke and made it into an unfunny, protracted slog:

I think it is pretty immediately self-evident just how much more poorly this scene plays out relative to its earlier counterpart. This joke about the body is just painfully unfunny. All Leslie Jones has to do when asked if there is a body in the back is say “Let me check” and walk four feet and check. And yet there’s this weird back-and-forth between the four characters that really doesn’t make any sense at all and completely falls flat as a result. None of it feels recognizable. People do not really act like this, even within the context of screwball comedy movies. Of course, the film can’t resist a sort of smarmy, quippy remark from one of its characters (“Yeah I can think of seven good uses of a cadaver to-day”) because that’s the sort of thing that sells in today’s cinematic market. It’s all entirely predictable.

The mistake here is thinking that outlandishness and novelty is a substitute for normalcy—that comedy is only capable if you’re firing on all cylinders and acting out some sort of madcap routine. Most of the great comedies of past years—indeed, the great movies of decades past—recognized that the deftest kind of character depiction is often that which hews as closely as is reasonably possible to the recognizable, the typical, the ordinary; you can do a great deal within those relatively broad parameters.

Mainstream movies are increasingly uninterested in that. We are at present in an unserious age of cinema, one in which the movie’s most interesting and meaningful forms and modalities have been abandoned in favor of very cheap and ultimately empty trivialities. There is a reason why the most popular movies every year tend to be nearly all sequels and reboots: Nobody is making original, captivating films anymore, not like they used to. In the absence of genuinely good cinema, the scraps of familiarity are all people have left to enjoy.

Critics might argue that this entire exercise is pedantic, that a few examples of crummy movie conventions can’t possibly hope to capture the whole spectrum of the current era of motion pictures. Hey, maybe that’s true. You know what else is true? Movies continue to suck. We all know it. There’s a reason that last year’s Top Gun: Maverick was hailed at several outlets as the “return of the blockbuster” and Tom Cruise was touted as “the last movie star:” Because these things don’t really exist anymore, not in the bright and dazzling and high-quality way they used to.

The Top Gun sequel was not, in fact, “the return of the blockbuster.” There are at present no incentives to make what moviegoers used to consider “blockbusters,” those broadly appealing mainstream movies featuring instantly recognizable stars with household names. And as Jennifer Aniston astutely observed last year, there are “no more movie stars,” either. It’s increasingly just an endless run of mediocrity and bad jokes and oversaturated pastel, all of it playing out at 60 smash cuts per minute.

Maybe the movie will experience a return to form at some point. Maybe. It would require a radical shift in priorities in the part of viewers, one I have trouble imagining. At the very least it would require millions of people to stop giving their money to these awful forms of sub-art. But people seem mostly okay with that. The problem, ultimately, isn’t that filmmakers are making these movies; it’s that moviegoers want these movies to be made. There is only so much critical analysis you can do before you run up against the hard facts of consumer choice. These new movies are not going anywhere, because moviegoers aren’t going anywhere—except to these movies, of course. Hopefully they will be rewarded with many more scenes of Avenger superheroes having cocktails together, because in this landscape there is not much else to look forward to.

To anyone who watched the Independence Day sequel, I'm sorry for your loss.

Great essay.

I disagree with only the final paragraph! I think it's clear that audiences don't really want this, which is why even these big Marvel and Star Wars movies are underperforming. They still make a stupid amount of money, but it's more because that's all that's available.

The problem is media consolidation. There aren't filmmakers out there making interesting or risky movies because no one will fund that. Definitely Disney (which produces like half of movies currently made) is not going to hand someone like Paul Thomas Anderson (let alone a filmmaker like Paul Thomas Anderson was in the early 90s - unknown and untested) 30-70 million dollars to make a movie.

I know people who work as screenwriters who have been in meetings where they pitch a script and 9 times out of 10, the first question asked is: Can we fit this into IP we already own?

Studio executives have decided that people don't want anything that takes risk and they're not willing to make the financial risk and so you end up with the Barbie movie or the 30th Marvel movie or whatever else.